Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 5 of 5: How do We Create a Diverse and Stable Economic System?

Welcome to the belated final installment of our five part analysis. We have been working towards the title’s conclusion by seeking an answer to the following question.

What difference between natural / social, and economic, systems causes one to tend towards diversity and stability, and the other, uniformity and instability?

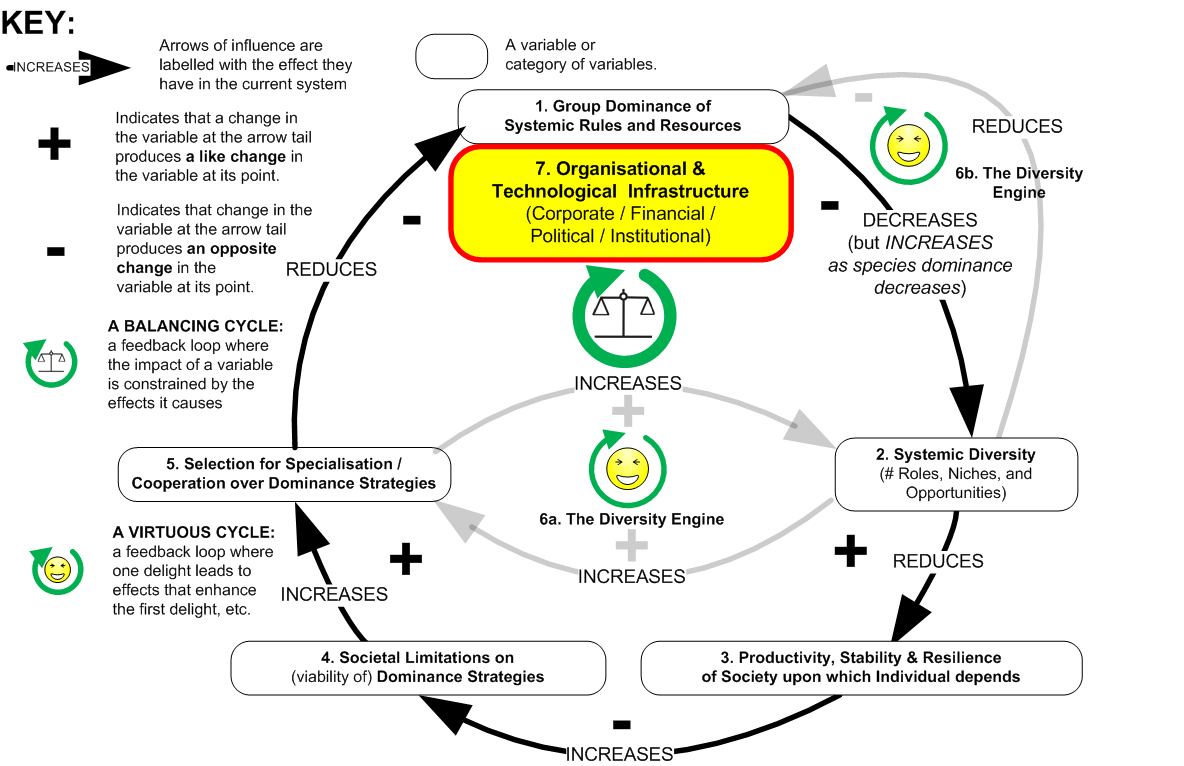

In installments 1, 2 and 3, we proposed that in natural / social systems a species or ‘group’ seeking total domination of their environment are constrained and, ultimately, destroyed by the impoverishing and destabilising effects of their actions on the systems upon which their own survival depends, thus leaving the arena open for dynamics that promote diversity and long-term stability (see previous installments if you need an explanation of the model below).

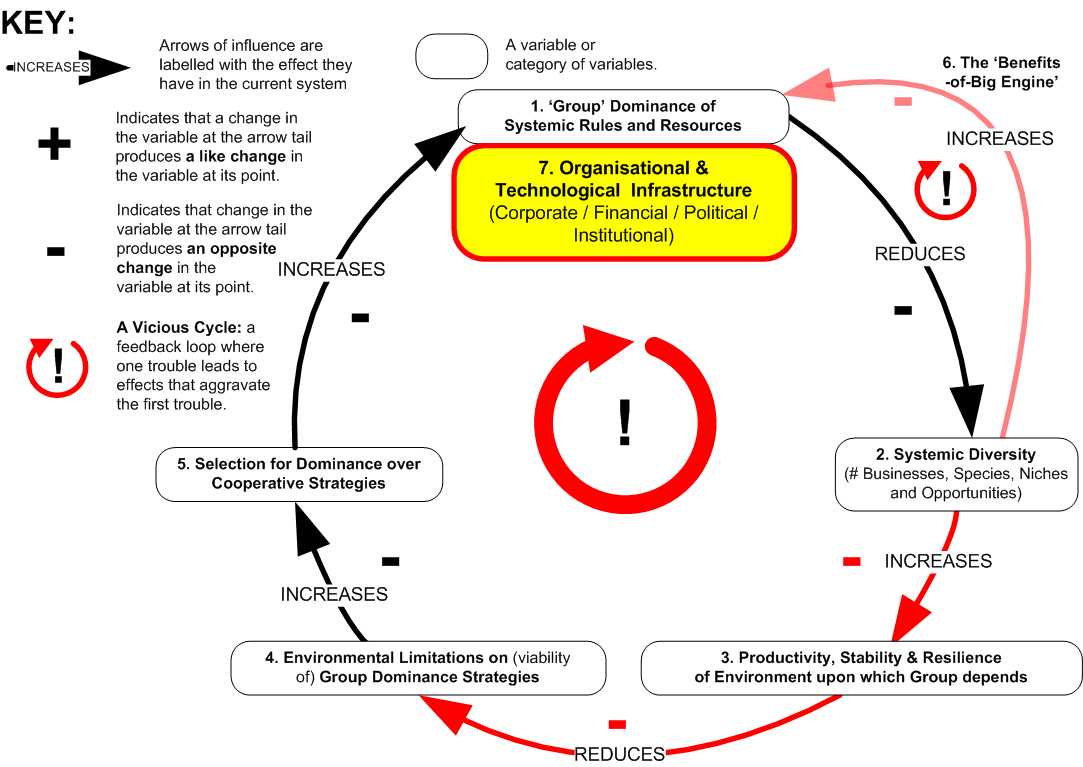

In installment 4 we suggested that the current economic system displays a reverse trend towards uniformity and instability because it allows the small ‘groups’ at the helms of corporations to gain increasing wealth and power from disintegrating social / natural systems without ever personally experiencing the environmental backlash of their actions. (see installment 4 if you need an explanation of the model below).

To clarify, this shouldn’t be taken as a demonisation of businessmen. Some individuals are naturally entrepreneurial, status-driven or materially-oriented, and the prosperity and order we have come to enjoy in recent centuries are largely indebted to their spirit and energy. Indeed, there are few among us that wouldn’t pass up a lottery win and the prestige, security and freedom it affords.

To clarify, this shouldn’t be taken as a demonisation of businessmen. Some individuals are naturally entrepreneurial, status-driven or materially-oriented, and the prosperity and order we have come to enjoy in recent centuries are largely indebted to their spirit and energy. Indeed, there are few among us that wouldn’t pass up a lottery win and the prestige, security and freedom it affords.

However, in the current era, unconstrained profit-and-power motivated vicious cycles represent a mortal threat to our freedom of choice, quality of life and, most urgently, our planet’s life systems. If the virtuous feedback mechanisms that promote diversity and stability in natural / social systems do not function naturally in the current economic system, then they they must be imposed artificially with due haste. But how?

First let’s summarise, in a nutshell, the problem to be resolved…

In the current economic system, dominant ‘groups’ are able to benefit from abusing the diversity and stability of socioenvironmental systems without ever experiencing negative feedback from their actions.

Although many possible interventions occurred to Arkadian whilst writing this series, a coherent regulatory model, which offered an unobjectionable, easy transition from the current economic system was not so easy to imagine (the reason why the final installment has been so long in coming!). Happily, a fully-formed (40yr old) solution presented itself recently in Chapter 19 of ‘Small is Beautiful’, courtesy of the genius of economist, E.F. Schumacher (pictured left).

The Schumacher Business Model, stated simply, rests on 2 systemic ‘tweaks’: (1) limiting the number of people a single corporate entity can employ and (2) introducing meaningful public ownership and accountability into business structure and practice.

(1) Legally restricting corporation size by number of employees. It would seem reasonable that a ceiling should be dictated chiefly by evidence regarding effective human group size (see Dunbar’s number), say between 80-200 persons. Growth beyond the upper limit, Schumacher suggests, should entail the formation of new independent corporate units, which may be linked by joint stock. These restrictions would enable each employee to ’embrace the idea of the business as a whole’ and the value of their role therein, but most importantly to the current argument, it would ensure that ‘the group (i.e. The Board)’ couldn’t claim ignorance of the details of their company activities and, thus, could reasonably be held personally accountable for abuses.

Furthermore, constraining size, particularly when the exploitation of natural / social resources is involved, is also more likely to physically ground a corporation in a local environment. Bringing ‘the group’ closer to their employees and the raw coal face of their realworld transactions is likely to increase their susceptibility and responsiveness to negative socioenvironmental feedback both internal and external to their organisation. It is also liable to curb the scale of impacts of which a single corporate vehicle is capable.

All very well, the cynics may cry, but what of the ‘groups’ with the thicker skins and thinner moral fibre?

(2) Public Ownership and Accountability. Schumacher advises we put an end to annual corporate taxation (a proposition not disagreeable to most businessmen!). In its place he proposes that for every share sold privately by a company, a further share is issued to the public. Thus, as owner of 50% of the company, we’d collectively receive half of any dividends if and when they are paid out to shareholders (he argues that when a company grows beyond a certain size it loses its ‘private and personal character’ and thus can be considered, in a sense, a public enterprise anyway).

To avoid disruption, our public equity wouldn’t allow us any voting rights in everyday business decision-making. It would, however, entitle us to attend Board meetings as an observer and, if the actions of the business were deemed to run counter to the public or environmental interest, we could apply to a court to get dormant voting rights activated.

To avoid disruption, our public equity wouldn’t allow us any voting rights in everyday business decision-making. It would, however, entitle us to attend Board meetings as an observer and, if the actions of the business were deemed to run counter to the public or environmental interest, we could apply to a court to get dormant voting rights activated.

To exercise these corporate responsibilities, Schumacher proposes the creation of independent citizen bodies funded from local business dividends. These ‘Social Councils’ would be split into four equal parts: three would have their members nominated by local trade unions, professional, and environmental, organisations, with the final quarter being drawn randomly from local residents in the manner of jury service. Involvement in management processes would, of course, be bound by strict confidentiality agreements.

Schumacher’s model brings socioenvironmental feedback directly into the Board room both as a ‘possibility in the background’ and, when necessary, as a real, prevailing constraint.

It is Arkadian’s prediction that, over time, exposing the ‘groups’ at the corporate helm to these balancing dynamics would drive a new trend towards macroeconomic diversity and stability, and greater corporate responsibility for the integrity of the natural environment (by triggering the ‘Diversity Engine’, described in installments 1, 2 and 3). And to top it all, it would require minimal design and economic / legal restructuring because, in the main, the model utilises existing frameworks and practices.

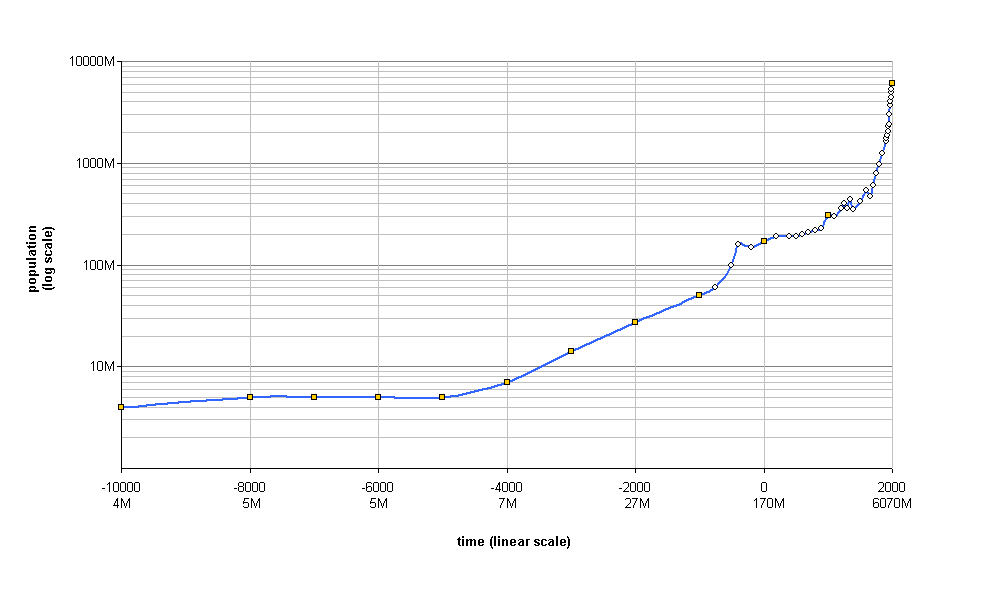

To conclude, effective corporate regulation is not just a Utopian nice-t0-have. It took till 1960 for World Population to hit 3bn. It has grown by 1bn approximately every 12yrs since, probably hitting the 7bn mark earlier this year. There are more human beings to house and feed today than have ever lived before. Presently, we have just over 2 acres of workable land each, 4x less than a century ago, and this is shrinking each moment as corporate activities and climate change destroy the natural world, and population continues to skyrocket.

Resultant biodiversity loss, whilst often second-ranked in current ‘problem’ trends is, as we’ve established, probably the most dangerous of all due to its inscrutable relationship with macroenvironmental instability. With extinctions currently at 1000x the background base rate, and predicted to rise to 10,000x over this century, we are very rapidly, and very blindly, removing the Jenga pieces of our life systems, largely for the sake of the short-term wealth creation of the small ‘groups’ of the corporate elite. History is littered with exemplars of total societal and environmental meltdown as the result of human impact on vulnerable ecosystems: Easter Island, The Mayans, The Pueblo Culture of the South Western USA, the Norse Greenland and Iceland colonies to name but a few. If we repeat the same mistakes globally, we may not get a second chance.

Resultant biodiversity loss, whilst often second-ranked in current ‘problem’ trends is, as we’ve established, probably the most dangerous of all due to its inscrutable relationship with macroenvironmental instability. With extinctions currently at 1000x the background base rate, and predicted to rise to 10,000x over this century, we are very rapidly, and very blindly, removing the Jenga pieces of our life systems, largely for the sake of the short-term wealth creation of the small ‘groups’ of the corporate elite. History is littered with exemplars of total societal and environmental meltdown as the result of human impact on vulnerable ecosystems: Easter Island, The Mayans, The Pueblo Culture of the South Western USA, the Norse Greenland and Iceland colonies to name but a few. If we repeat the same mistakes globally, we may not get a second chance.

Considering the twin pincers of population growth and biodiversity loss, it is quite evident that socioenvironmental stability and sustainability are our most important objectives for the c21st, bar none. Our very survival depends on achieving them and success is contingent upon economic and environmental policy which is underpinned by the principle of diversity=stability=good. If variety is both the spice and source of life, then we must put democratic pressure upon Government and business to make the small tweaks to our economic system necessary for it to produce abundance by its own workings.

For a fascinating and vitally important lesson in the importance of preserving and promoting biodiversity, Arkadian cannot recommend the video below more highly. Essential viewing for all inhabitants of Planet Earth.

1 Comment

Leave a comment to Evie Murray

Recent Posts

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 3: Placing Mother Nature First

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 4: Ego-as-Process

- Charlie Hebdo and the Immorality Loop

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt3 (S America: #2-1)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt2 (S America: #7-3)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt1 (Africa, Asia, Europe & N America)

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 4: Principles in Action

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 3: Freedom from the Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 2: The missing Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 1: The Campaign Complex

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 2: The Principal Themes (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 1: The Action Plan (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- What I Learned from Destroying the Universe

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 5 of 5: How do We Create a Diverse and Stable Economic System?

- The Root of all Evil: how the UK Banking System is ruining everything and how easily we can fix it.

- What is Occupy? Collective insights from a ‘Whole Systems’ Session with Occupy followers

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 4 of 5: Why does the current Economic System tend towards Uniformity and Instability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 3 of 5: Why does A Diverse System = A Stable System?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 2 of 5: Why does (did) Civilisation tend towards Diversity and Stability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 1 of 5: Why do Ecosystems tend towards Diversity and Stability?

Thank you Jamie, It seems like a very realistic approach and doo’able. Lets begin the process of getting this in place. I think Eric who will attend our meeting if back from his holidays has very similar ideas on this, questions on how to get it going will be the next step I think. What an amazing contribution. Well done.