Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 3 of 5: Why does A Diverse System = A Stable System?

Delighted that you’ve joined us for the third installment of our first Arkadian analysis for 2012, where over five short articles, we will show how we reached the series title’s conclusion by way of the following question: –

“What difference between natural / social systems and the current economic system causes the former to tend towards diversity and stability, and the latter, uniformity and instability?”

In Weeks 1 and 2, we investigated why ecosystems and ‘civilisation’ tend towards diversity and stability. It was proposed this was attributable to virtuous dynamics that promote long-term systemic stability and resilience by driving increasingly fine-grained specialisation / cooperation, whilst inhibiting environmental dominance by particular species or social ‘groups’.

Next week we will be putting forward an explanation as to why the current economic system displays the reverse trend but, for now, we thought it worthwhile to explain briefly the connection between diversity and stability. Why exactly does a change in the former result in a like change in the latter?

Put simply, in a diverse system, the health of the whole (‘productivity’) isn’t dependent on the performance of only a few parts.

For example, imagine a disadvantaged family where Dad is the only breadwinner. If he has an accident, no-one eats. If the house blows down in a storm, there’s no-one to rebuild it. Compare the situation with a second family where several other members also contribute to the household income. Because ‘productivity’ is distributed across several people, the overall family ‘system’ is much more able to adapt to an accident-prone Dad and / or a force majeure.

For example, imagine a disadvantaged family where Dad is the only breadwinner. If he has an accident, no-one eats. If the house blows down in a storm, there’s no-one to rebuild it. Compare the situation with a second family where several other members also contribute to the household income. Because ‘productivity’ is distributed across several people, the overall family ‘system’ is much more able to adapt to an accident-prone Dad and / or a force majeure.

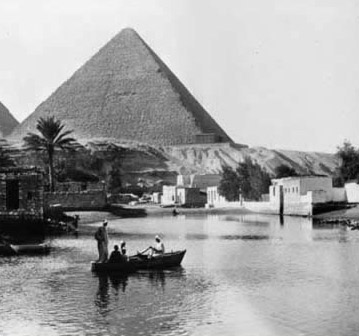

A classic instance of systemic over-dependency at a macro-societal level is Ancient Egypt, which teetered on a single variable: the annual flooding of the Nile (taken from the excellent ‘Water’ by Steven Solomon). The ‘inundation‘, as it was known, rejuvenated the plains with fertile silt and washed away soil poisons, to produce the most self-sustaining and fertile farmlands of the ancient world.

A classic instance of systemic over-dependency at a macro-societal level is Ancient Egypt, which teetered on a single variable: the annual flooding of the Nile (taken from the excellent ‘Water’ by Steven Solomon). The ‘inundation‘, as it was known, rejuvenated the plains with fertile silt and washed away soil poisons, to produce the most self-sustaining and fertile farmlands of the ancient world.

The exclusive focus of the political elite was water management: senior priest-managers led departments for overseeing dikes, canal workers and measuring river levels; and top dog, Pharaoh’s, fundamental godly responsibility was mastery of the flow of the great river.

Unsurprisingly then, the Nile and Egyptian history ebb and flow in perfect synchronicity. Without exception, the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms, as well as the later periods of Greek and Byzantine rule, bloom with the return of the regular cycle of flooding and crumple with climactic dry periods into centuries of disunity, chaos and foreign invasions. Thus, despite many environmental blessings, ultimately, the stability and resilience of this mighty civilisation and its elite were slave to the caprices of its one water source, in a way that a country with abundant springs, rivers and lakes could never be.

Our third and final example – the current economic downturn – illustrates uniformity and instability at a global level. Here, the world’s banking system was rendered so fragile by the interdependency of a few titanic banks and financial services firms, that massive external intervention was required to prevent total meltdown when one of them, Lehman Brothers, filed for bankruptcy in 2009. It is a crisis and an intervention for which we shall all suffer for many decades to come.

Our third and final example – the current economic downturn – illustrates uniformity and instability at a global level. Here, the world’s banking system was rendered so fragile by the interdependency of a few titanic banks and financial services firms, that massive external intervention was required to prevent total meltdown when one of them, Lehman Brothers, filed for bankruptcy in 2009. It is a crisis and an intervention for which we shall all suffer for many decades to come.

But why had the economic system not behaved like the natural / social systems we looked at in Weeks 1 and 2, and become increasingly diverse and stable as it expanded? We hope you’ll drop in next Friday to find out.

Leave a comment

Recent Posts

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 3: Placing Mother Nature First

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 4: Ego-as-Process

- Charlie Hebdo and the Immorality Loop

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt3 (S America: #2-1)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt2 (S America: #7-3)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt1 (Africa, Asia, Europe & N America)

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 4: Principles in Action

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 3: Freedom from the Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 2: The missing Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 1: The Campaign Complex

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 2: The Principal Themes (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 1: The Action Plan (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- What I Learned from Destroying the Universe

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 5 of 5: How do We Create a Diverse and Stable Economic System?

- The Root of all Evil: how the UK Banking System is ruining everything and how easily we can fix it.

- What is Occupy? Collective insights from a ‘Whole Systems’ Session with Occupy followers

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 4 of 5: Why does the current Economic System tend towards Uniformity and Instability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 3 of 5: Why does A Diverse System = A Stable System?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 2 of 5: Why does (did) Civilisation tend towards Diversity and Stability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 1 of 5: Why do Ecosystems tend towards Diversity and Stability?