Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 4 of 5: Why does the current Economic System tend towards Uniformity and Instability?

Welcome to the fourth and penultimate episode of a five-part Arkadian analysis which works towards the conclusion in the series title by seeking the answer to a simple question: –

“What difference between natural / social systems and the current economic system causes the former to tend towards diversity and stability, and the latter, uniformity and instability?”

In Weeks 1 and 2, we explored why ecosystems and ‘civilisations’ tend towards diversity and proposed virtuous dynamics (the ‘Diversity Engine’) that power increasingly fine-grained specialisation / cooperation, whilst inhibiting environmental dominance by particular species or social ‘groups’. Last Week, we looked at three examples at different ‘levels’ (social group, societal, global) which illustrated why overall systemic stability and resilience, and, thus, the common good, depends on a shared responsibility for productivity produced by this trend.

Today, we aim to get the crux of the issue at the heart of this series by investigating why the current global economic system behaves in the opposite way.

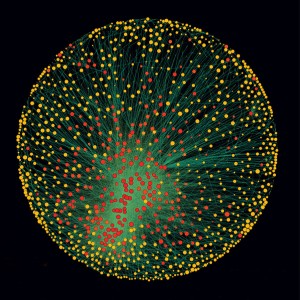

The last few decades have seen a dramatic global trend towards economic uniformity across most market sectors – most notably and worryingly, finance, media, food and agriculture, and manufacturing. A recent systems analysis by PLos One revealed that a network of 1318 companies directly represent a quarter of global operating revenues and, indirectly, via shareholdings in blue chips and manufacturing, a further 60%. Of these, a super-group of 147 companies, mostly financial institutions controls 40% of the total wealth in the system.

The last few decades have seen a dramatic global trend towards economic uniformity across most market sectors – most notably and worryingly, finance, media, food and agriculture, and manufacturing. A recent systems analysis by PLos One revealed that a network of 1318 companies directly represent a quarter of global operating revenues and, indirectly, via shareholdings in blue chips and manufacturing, a further 60%. Of these, a super-group of 147 companies, mostly financial institutions controls 40% of the total wealth in the system.

This homogeneity has also correlated with a spectacular increase in the scale and financial muscle of global corporations. A 2002 UNCTAD analysis, which used the sum of salaries and benefits, depreciation and amortization, and pre-tax income to compare firms with the GDP of countries, found that a third of the world’s 100 largest economic entities were transnational corporations. The biggest, Exxon, rivaled the economies of Chile or Pakistan; Philip Morris was on a par with Tunisia, Slovakia and Guatemala; and a more recent study research shows General Motors, DaimlerChrysler, Shell, and Sony to outsize Denmark, Poland, Venezuela, and Pakistan, respectively.

Many other corrosive trends have gone hand-in-hand with this expansion. According to statistics gathered by the New Economics Foundation, income inequality is now higher than at any other time in human history with the CEOs of the 365 biggest US companies earning over 500x that of the average employee. Corporate strategies to augment profits – outsourcing, temporary employment contracts, mechanisation and process efficiency – have eroded wages, job satisfaction and security, and human labour productivity, with the world’s biggest 200 transnationals now accounting for a third of world economic activity but employing less than 0.25% of the global workforce.

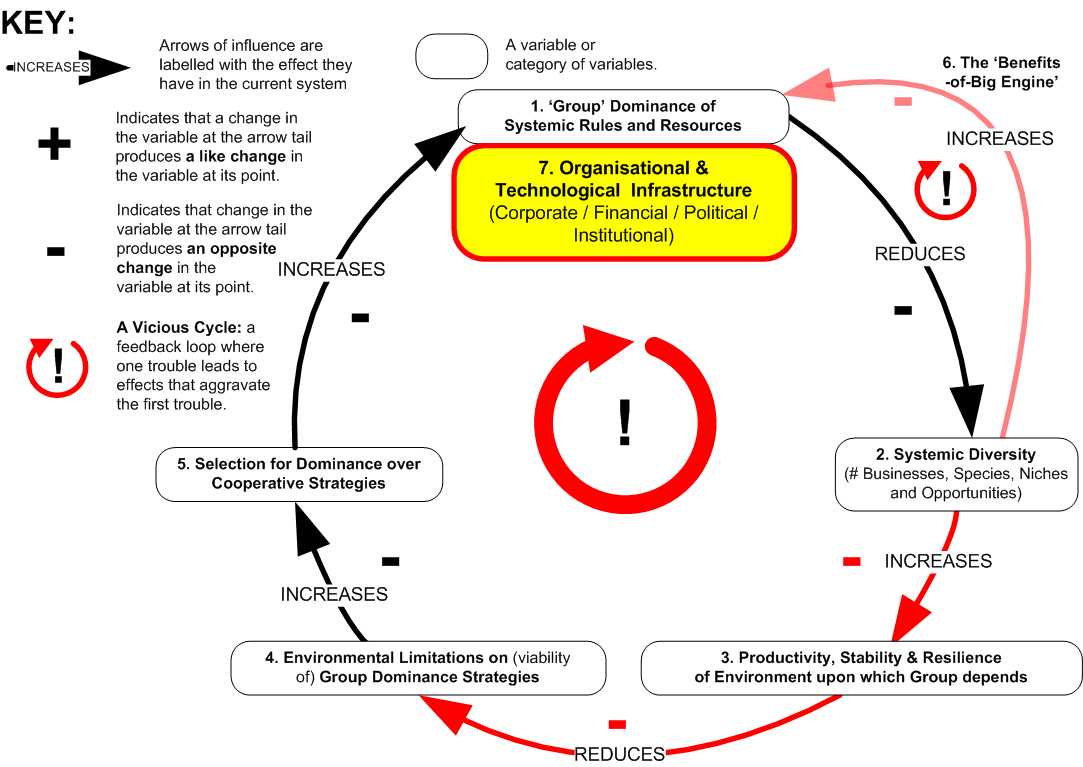

So what are the dynamics underpinning this pernicious trend? MODEL 3 of our analysis below proposes an answer (N.B. If you have trouble reading the text, click on the diagram to open it in a new browser tab and then refer back to the explanation here).

Whilst Model 3 involves more-or-less identical variables to the Models 1 (Ecosystems) and 2 (Civilisations) we explored in Weeks 1 and 2 respectively, there are several critical differences. Firstly, we broaden the definition of ‘diversity’ to include both socioeconomic and natural systems. Secondly, the term ‘group’ (which referred to political elites in Model 2) now refers specifically to the small alliance of people for whom a given corporation is a vehicle of wealth-creation: board executives, major shareholders, higher management and, to a lesser degree, senior employees, i.e. the people who don’t lose their jobs or bonuses during cutbacks.

Thirdly, and most fundamentally, is a change in the polarity of the two arrows (coloured red) connecting variables (2), (3) and (4). Unlike dominant species in ecosystems and ruling elites in political systems, these ‘groups’,empowered by (7) policy and infrastructure that enable vast geographical reach, promote their self-interest and shield them against personal accountability for abuses, are able to reduce systemic diversity without their actions having corresponding negative effects on the stability and resilience of their own local environment.

Thirdly, and most fundamentally, is a change in the polarity of the two arrows (coloured red) connecting variables (2), (3) and (4). Unlike dominant species in ecosystems and ruling elites in political systems, these ‘groups’,empowered by (7) policy and infrastructure that enable vast geographical reach, promote their self-interest and shield them against personal accountability for abuses, are able to reduce systemic diversity without their actions having corresponding negative effects on the stability and resilience of their own local environment.

Indeed, (3) the greater the ‘group’s’ impact on diversity, the more prosperous and secure their personal environment becomes. Thus, in the current economic system, (1, 4, 5 and 6) the drive for dominance of rules and resources is invigorated by growing wealth, social mobility and political influence, unlike ecosystems and civilisations, where it was curtailed by its weakening and destabilising impact on the environment And so it turns: not a Balancing Loop, but a Vicious Circle: a feedback loop where one trouble leads to effects that aggravate the first trouble, and so on.

To exacerbate problems, the absence of limiting environmental feedback also reverses the dynamics of the ‘Diversity Engine’, turning it into its ominous alter ego: a Vicious Circle we’ve named the (6) ‘Benefits-of-Big Engine’.

Here, instead of a trend towards economic diversity facilitating healthy competition and new business opportunities, and making market domination progressively more difficult, a small group of dominant players is able to harness ever greater resources, economies-of-scale and mechanisms of influence (price, lobbying, political office, advertising, media, academia) to overcome existing competition and render future challengers increasingly futile and improbable.

Disturbingly, whilst in nature / society the weaknesses and instability resulting from systemic impoverishment ultimately defeat the dominant species and ruling groups responsible, thereby facilitating a new order, in the current economic system they increasingly further the interests of the corporate ‘groups’ that have caused them.

These giants can downsize, buyout or price-out smaller floundering competition, and their huge economic significance means that, even if things get really bad, national governments are likely to intervene rather than risk the impact of bankruptcy. As touched upon in Week 2, the crisis-stricken financial sector is a perfect example, where after the panic of insolvencies, public bailouts and recession, a run of mergers and buyouts gave birth to a more monolithic, powerful and fragile banking system than ever before.

Possibly the darkest characteristic of ‘The Benefits of Big’, however, is that the larger and more ubiquitous these corporate vehicles become, and the more competitively priced their products and services, the more difficult it becomes for us to avoid participating in their expansionary activities.

Possibly the darkest characteristic of ‘The Benefits of Big’, however, is that the larger and more ubiquitous these corporate vehicles become, and the more competitively priced their products and services, the more difficult it becomes for us to avoid participating in their expansionary activities.

Thus, as customers, suppliers and employees, we all unknowingly or unwillingly, become complicit in dynamics that increasingly impoverish and endanger the systems upon which we depend.

In short, in the current economic system there appears to be no constraint on the wealth-creation of ‘groups’ at the helms of corporations other than a total socioenvironmental meltdown.

Happily, there is much we can do to change this. We hope you’ll join us next Friday for our final installment, when we shall use what we’ve learned from the virtuous ‘Diversity Engine’ of ecosystems / civilisations to propose interventions that could reverse the vicious ‘Benefits of Big Engine’ and create a self-sustaining economic system that benefits people and planet.

Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 2 of 5: Why does (did) Civilisation tend towards Diversity and Stability?

Hello again and thanks for joining us for the second in a five-part Arkadian analysis, where we show how we reached the conclusion of the title series by way of one simple question: –

“What difference between natural / social systems and the current economic system causes the former to tend towards diversity and stability, and the latter, uniformity and instability?”

Last week, we explored why natural systems tend towards diversity and stability. Dynamics were proposed (the ‘diversity engine’) that, through natural selection, weed out species that strive for environmental supremacy and favour those that cooperate, specialise and, by doing so, facilitate opportunities for new evolutionary adaptations.

This week we shall take a brief look at one creature that, at first sight, appears to operate outside these dynamics: Homo Sapiens. What is it about the human species that enables it to dominate ecosystems without appearing to suffer the constraining feedback?

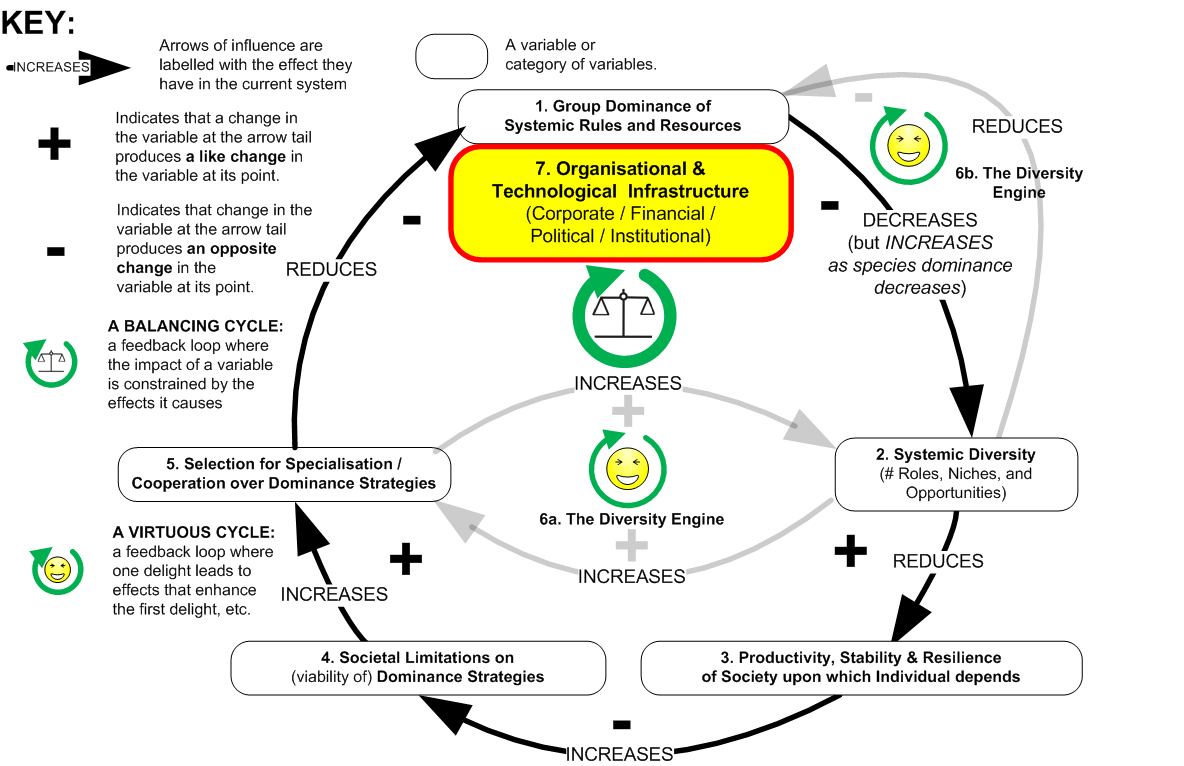

MODEL 2 of our analysis below proposes an answer (N.B. If you have trouble reading the text, click on the diagram to open it in a new browser tab and then refer back to the explanation here).

If you joined us last week, you’ll see immediately that MODEL 2 is more-or-less identical to MODEL 1. We propose that civilisation’s social matrix shares the same stabilising dynamics of natural systems and that these confer the ability to adapt more reflectively and effectively to environmental constraints.

Significantly, world population only began to increase appreciably with the order provided by the first civilisations from around 1,000 BC onwards. Many historians argue that the political infrastructure of Ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, India and China initially emerged from local organisational efforts to coordinate large scale (particularly, irrigation) ecosystem management, rather than these projects being the initiative of an already-ensconced ruling ‘group’.

It is the Arkadian view that the managerial perspective born from these projects enabled infrastructural and organisational tweaks that, in turn, facilitated a trend towards increasing division of labour and role / skill / knowledge specialisation, and it was this burgeoning socioeconomic diversity and interdependence rather than the direct actions of a ruling group that provided the stability required for civilisation to flourish.

Indeed, as many power / status / wealth hungry ruling groups have since discovered to their own detriment, enduring political success hinges not on their own genius, but on the assiduous maintenance of this diversity engine. As a general rule (and as with the overbearing species we looked at last week), (1 and 2) the greater the impact of the ‘group’s’ rule and resource dominance on local socioeconomic (and environmental) diversity, (3 and 4) the more unproductive, unstable and weaker their regime tends to become.

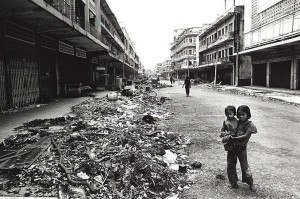

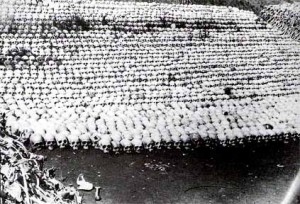

A tragic example of this self-defeating governmental dynamic is Cambodia under the communist Khmer Rouge. Seizing power in 1975 in the wake of 4yrs of destabilising bombings by US and Vietnamese forces, they immediately shut down all transport and information links with the outside world, declared private property illegal, and established a ‘Year Zero’ for Cambodian society.

Their ‘Agrarian Revolution’ – an economic model founded on the single pillar of self-sufficient rice production – was to have a cataclysmic impact on all aspects of systemic diversity: social, cultural, economic and environmental.

Their ‘Agrarian Revolution’ – an economic model founded on the single pillar of self-sufficient rice production – was to have a cataclysmic impact on all aspects of systemic diversity: social, cultural, economic and environmental.

All those who threatened their ideological dominance were murdered or exiled – ethnic and religious minorities, journalists, doctors, educators, writers, anyone with an education – obliterating vital cultural, intellectual and skill resources.

Urban populations were forced to leave cities, towns and former roles behind to slash-and-burn virgin rain forest, set up collective farms, and take responsibility for rice production, whilst the thousands of male peasant farmers with the requisite know-how were press-ganged into military service.

Naive farming communities went hungry rather than risk retribution for failing to meet the Government’s exorbitant rice targets, which soon resulted in a precipitous deterioration in output. Almost a quarter of the population died of starvation or execution under the regime, a disproportionate number of which were male.

Naive farming communities went hungry rather than risk retribution for failing to meet the Government’s exorbitant rice targets, which soon resulted in a precipitous deterioration in output. Almost a quarter of the population died of starvation or execution under the regime, a disproportionate number of which were male.

Within three-and-half years, the loss of diversity and productivity had rendered the Khmer Rouge’s power base so weak, they were easily overthrown by a Vietnamese invasion.

30 years later, the Cambodian ‘system’ is still suffering. Political instability has resulted in 4 coups over the interim period. The country still has the highest proportion of women (65%), malnutrition and physical disability in South-East Asia (the latter attributable primarily to the Khmer Rouge’s estimated 4-6m unexploded mines).

The country’s economy remains dependent on tenant farmers involved in backbreaking rice production for minimum profit. Necessarily, many of these are women, creating further societal tensions by violating customary rules and roles of a traditionally patriarchal society. International development experts argue that, despite the potential for a full recovery, without external intervention the Cambodian socioeconomic system will struggle to escape the impoverished, fragile state in which it was left by the Khmer Rouge.

Conversely, ‘laissez faire’ ruling groups, such as The Ancient Greeks and Romans, that implemented policy and infrastructure which nurtured the (5/6) ‘socioeconomic diversity engine’ tended to produce history’s more enduring and resilient regimes. For example, in the mid c14th a nascent Western European civilisation – arguably, the most pluralistic, productive and market-driven the world had yet seen – successfully weathered a perfect storm of catastrophe that would have devastated a weaker social system, including climactic cold spells, famines, widespread peasant revolts, The Black Death, and an overall loss of quarter of the population.

Conversely, ‘laissez faire’ ruling groups, such as The Ancient Greeks and Romans, that implemented policy and infrastructure which nurtured the (5/6) ‘socioeconomic diversity engine’ tended to produce history’s more enduring and resilient regimes. For example, in the mid c14th a nascent Western European civilisation – arguably, the most pluralistic, productive and market-driven the world had yet seen – successfully weathered a perfect storm of catastrophe that would have devastated a weaker social system, including climactic cold spells, famines, widespread peasant revolts, The Black Death, and an overall loss of quarter of the population.

Nevertheless, (6b) although these ‘laissez faire’ strategies yielded prosperity for ruling groups, they also entailed a diminishing of their control over rules and resources as increasingly pluralistic and influential populations demanded ever greater democratic freedoms, rights and representation.

As we shall discuss in Week 4, this shift would ultimately give rise to a global economic elite whose power, and impact on diversity and stability, would dwarf that of any political ‘ruling group’. However, before we do, we thought it worth taking a moment to understand why it is that an ecosystem or ‘civilisation’ is more stable if it is diverse? Hope you’ll join us next Friday to find out.

Recent Posts

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 3: Placing Mother Nature First

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 4: Ego-as-Process

- Charlie Hebdo and the Immorality Loop

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt3 (S America: #2-1)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt2 (S America: #7-3)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt1 (Africa, Asia, Europe & N America)

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 4: Principles in Action

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 3: Freedom from the Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 2: The missing Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 1: The Campaign Complex

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 2: The Principal Themes (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 1: The Action Plan (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- What I Learned from Destroying the Universe

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 5 of 5: How do We Create a Diverse and Stable Economic System?

- The Root of all Evil: how the UK Banking System is ruining everything and how easily we can fix it.

- What is Occupy? Collective insights from a ‘Whole Systems’ Session with Occupy followers

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 4 of 5: Why does the current Economic System tend towards Uniformity and Instability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 3 of 5: Why does A Diverse System = A Stable System?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 2 of 5: Why does (did) Civilisation tend towards Diversity and Stability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 1 of 5: Why do Ecosystems tend towards Diversity and Stability?