Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 1: The Action Plan (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

This article is the first in a 4 part series relating to a soft-systems workshop Arkadian ran at Futures Connections 2012. The first 2 parts deal primarily with the outcomes of the session, whilst in the latter 2, Arkadian will be setting out some personal thoughts resulting from the analysis.

Participants were 20 PhD candidates from universities across Scotland, representing a broad variety of disciplines. All were conducting Research on the theme of Sustainable Development.

Since Futures Connections, the outcomes of this workshop have informed the decision-making of another project in which Arkadian is involved: An Tearman, on the Isle of Bute. An Tearman is an experiment in enacting a new socioeconomic model (‘Wisdom Economy’) involving a broad range of stakeholders. A prototype ‘blueprint’ heavily influenced by Permaculture principles is slowly emerging.

Since Futures Connections, the outcomes of this workshop have informed the decision-making of another project in which Arkadian is involved: An Tearman, on the Isle of Bute. An Tearman is an experiment in enacting a new socioeconomic model (‘Wisdom Economy’) involving a broad range of stakeholders. A prototype ‘blueprint’ heavily influenced by Permaculture principles is slowly emerging.

As the ideas generated by the workshop have contributed to the An Tearman project, so too have Arkadian’s learnings fed back into the current analysis, impacting on interpretations, and resulting in some development of the original workshop material, particularly in Parts 2, 3 and 4.

Next episode, we shall be discussing 4 Themes that pervaded the discussion, and in the last two installments, we’ll explore some ideas pertaining to the session outcomes. However, to begin we will outline the aims and structure of the workshop and describe its main outcome: An Action Plan for seeding a Viable Alternative.

The session’s Overarching Aim was:

WHAT?: To seed nationwide sustainable development.

HOW?: By building a self-sufficient and sustainable Community which demonstrates an inspiring, working model of a viable alternative to the current economic system.

WHY?: Because if we desire a tolerable future, there is an urgent necessity to begin our transition to a sustainable economy.

Participants were asked to consider 3 questions:

WHAT Personal Project would you bring to this Community?

HOW would it contribute to the Overarching Aim?

WHY is it important?

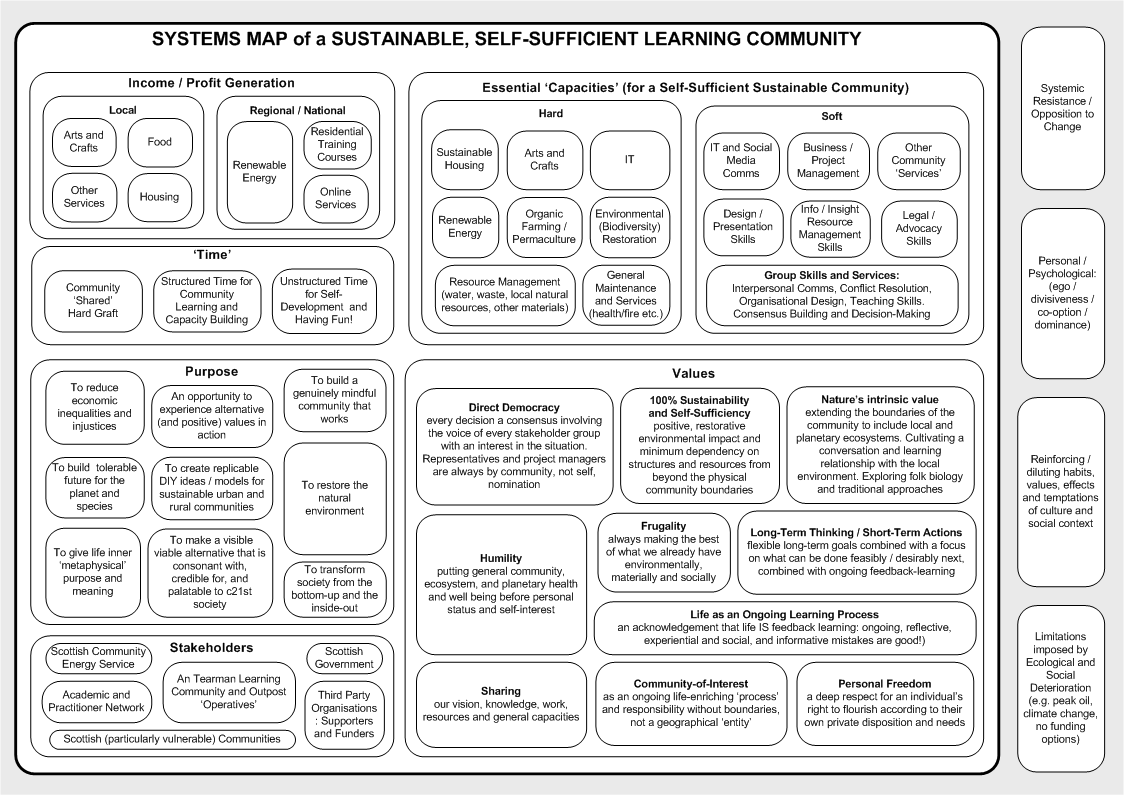

Responses were written on Post-Its in private and stuck randomly on a wall in What? / How? / Why? groups. The result fueled the group discussion. A Systems Map representing rough categories for the Post-Its and main topics of conversation appears below.

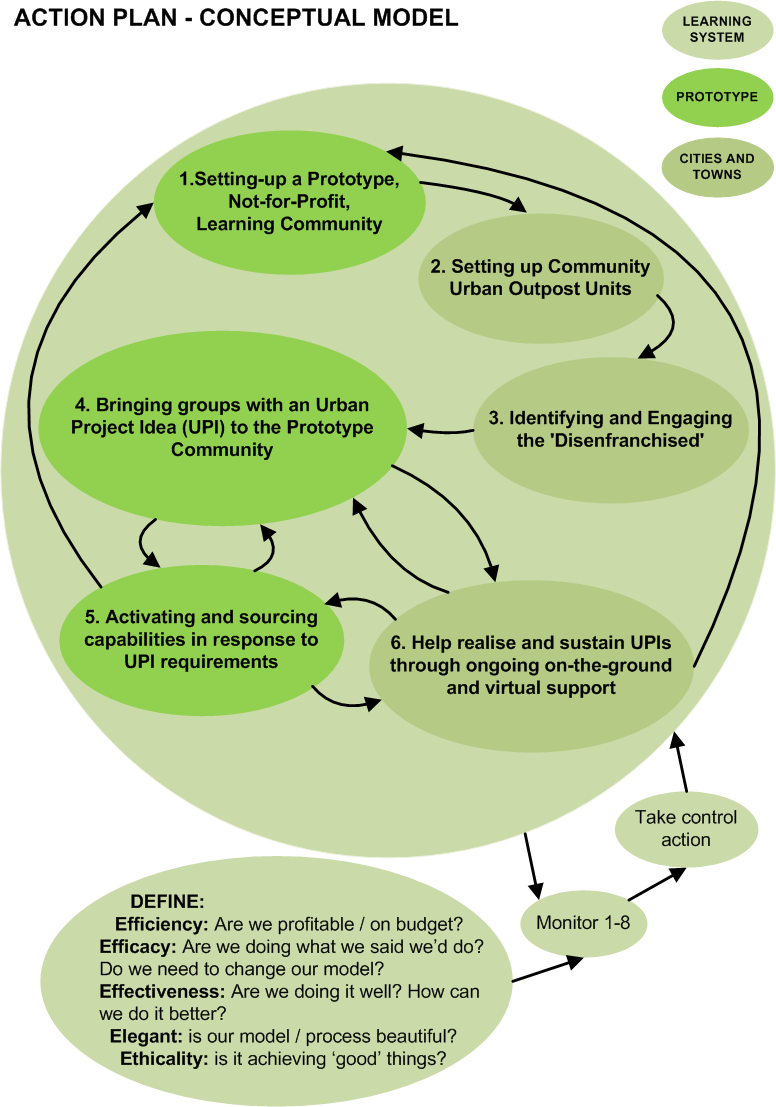

The main outcome of the session, unexpectedly, was an Action Plan for seeding nationwide sustainable development. This was as follows:

1. Set-up a Prototype Not-for-Profit Learning Community, which incorporated all the essential capacities of a nationwide sustainable Viable Alternative to the current economic system (see Systems Map: Essential ‘Capacities’). In other words, a ‘whole-system’ Prototype in miniature.

The original Community is envisioned as a cross-pollination of practical experiment and virtual network. At the outset the burning objective of the practical experiment is to generate zero impact revenue streams and become profitable (see Systems Map: Income / Profit Generation).

The virtual network is comprised of experts representing a wide variety of disciplines and experiential backgrounds who, whilst unable to commit substantial time to the practical experiment, are willing to contribute to decision-making whenever situation-specific expertise is required.

Community Time is split equally three ways:

(i) Collaborative physical transaction with the natural environment.

(ii) Structured time for community activities and decision-making. While this also includes the management of social groups and events, the major proportion of this time involves mindful and transparent group reflection upon both the practical experiment and social dynamics. Models, measures-of-success and next step actions are then co-calibrated in response to what has been learned.

Overarching decision-making and consensus-building are all highly-structured processes. They are third-party facilitated and knowledge is externalised using visual tools so as to depersonalise and depolarise opinion. All members are always involved, irrespective of subject, age or expertise. Thus, judgments and learning are informed by the broadest diversity of experience, and the emerging blueprint for the Viable Alternative is shared by all.

(iii) Unstructured time for personal development according to individual inclination. Spiritual, knowledge and skill development, leisure and recreational activities, time for special relationships, FUN? This is ‘You’ time, however you wish to spend it.

One of the central aims of the physical experiment is to generate a minimum of 4 free days every week for (ii) and (iii). Whilst profitability is undeniably important, it plays, and will always play, second fiddle to the meeting of the Community’s deeper non-material needs.

2. Setting up Community Urban Outpost Units. Now that our Prototype is stable, we use some of our assets to fund the despatch of ‘advocates’ to cities and large towns. As urban areas are where the current economic system is most resistant to change and its inequities are suffered most acutely, we believe it is here that successful exemplars of a Viable Alternative will achieve the most resonance.

2. Setting up Community Urban Outpost Units. Now that our Prototype is stable, we use some of our assets to fund the despatch of ‘advocates’ to cities and large towns. As urban areas are where the current economic system is most resistant to change and its inequities are suffered most acutely, we believe it is here that successful exemplars of a Viable Alternative will achieve the most resonance.

3. Engaging the ‘Disenfranchised’. Our advocates seek out and engage those groups that have a vested interest in a Viable Alternative. Perhaps the most obvious are young and disadvantaged peer groups, who have social capital but a bleak, hopeless future under the current system. We share the Prototype ‘blueprint’ with them, and encourage them to think about how they could positively transform their own environment in order to meet local needs.

3. Engaging the ‘Disenfranchised’. Our advocates seek out and engage those groups that have a vested interest in a Viable Alternative. Perhaps the most obvious are young and disadvantaged peer groups, who have social capital but a bleak, hopeless future under the current system. We share the Prototype ‘blueprint’ with them, and encourage them to think about how they could positively transform their own environment in order to meet local needs.

4. Bringing groups with an Urban Project Idea (UPI) to the Prototype. Groups with strong ideas, a willingness to learn, and a commitment to implement their UPI, are invited to the Prototype for experiential immersion in Community work, principles, values and decision-making. Stepping ‘outside’ of their everyday lives enables the groups to reflect upon their UPI with greater clarity and objectivity, and plan free of those shadowy constraints – models, relationships, habits, cues etc. – that hamper decision-making within context.

The group’s transition into participating in our emergent ‘blueprint’ is facilitated gently and mindfully. It is important we allow time for them to grasp the Prototype’s holistic model and processes, for their UPI to gestate, and for two fragile social systems (Prototype and group) to adapt to each other and reach the equilibrium necessary for them to operate effectively together.

5. Activating and sourcing capabilities in response to UPI requirements. When the group ‘feels’ sufficiently clear about their UPI, they are given the opportunity to conduct a Pilot within the Prototype.

The Community participates in related decision-making with openness and humility, seeing each UPI as an opportunity to learn and expand our own capacities. Mindful efforts are made to ensure that development is always under the direction of the group, and that our role remains that of a receptive enabler: sourcing and contributing specialism, materials and encouragement in response to the Pilot’s prevailing needs.

6. Helping realise the UPI through ongoing on-the-ground and virtual support. Upon completion of a successful Pilot, the group returns to their city or town to implement their UPI. By this time, they are equipped with ‘blueprint’ and experiences of a working Viable Alternative, and the skills to bring forth their own unique interpretation by transforming their local urban environment.

Throughout the realisation of their UPI, we continue to provide moral, specialist and financial support, and a sanctuary for retreat, review and restoration in the face of setbacks and systemic resistance.

UPIs are never colonies or subsidiaries, but rather lateral extensions of an expanding, highly interdependent Learning System. This emergent ‘Viable Alternative in action’ is held together by mechanisms that reinforce interrelationships: ritual gatherings where intent, principles and values are collectively reviewed, work and insights shared, and fun had. In the interim there are ‘dovetails’ – members whose role it is to participate in the decision-making processes of two constituent groups, thus facilitating the continuous flow of social learning through the whole system .

Although language may have represented this Action Plan as a linear sequence of stages, it was conceived as something more dynamic, reflective and feedback-driven, better captured visually in the Conceptual Model below.

And so ends our look at a possible ecology for a Prototype Viable Alternative, and an Action Plan for how it might seed nationwide transition bottom>up, inside>out and city>rural by way of an emergent Learning System.

To conclude this installment, possibly the most notable characteristic of the Action Plan on face value (particularly, one designed by a group of stakeholders operating at the leading-edge of sustainable development) is its humility. Perhaps when the scale, complexity and uncertainty of the challenge we face is spread across a wall for all to see, the only reasonable response is to design a system that acknowledges its own ignorance, creates the future one step at a time, and builds collective experience, reflection, experimentation and endeavour into its core DNA?

We hope you’ll join in a fortnight for Part 2, when we shall be exploring the four major themes that pervaded and informed the discussion of the Action Plan.

Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 5 of 5: How do We Create a Diverse and Stable Economic System?

Welcome to the belated final installment of our five part analysis. We have been working towards the title’s conclusion by seeking an answer to the following question.

What difference between natural / social, and economic, systems causes one to tend towards diversity and stability, and the other, uniformity and instability?

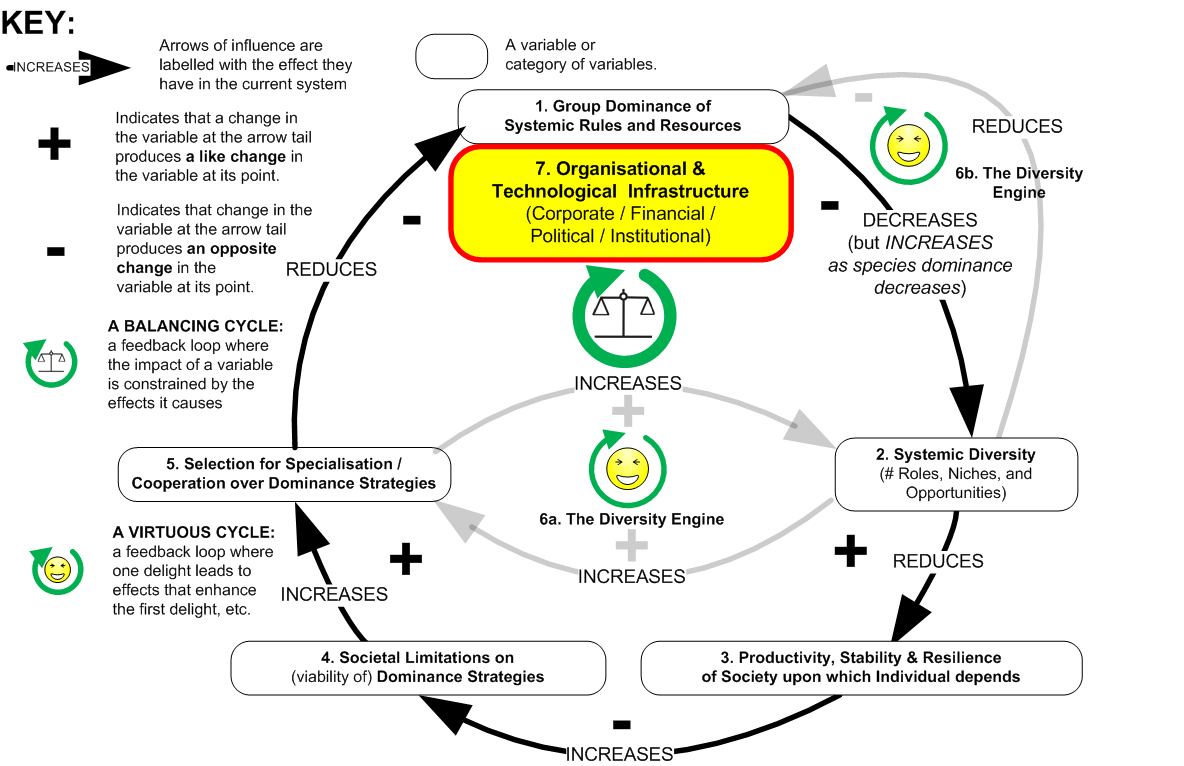

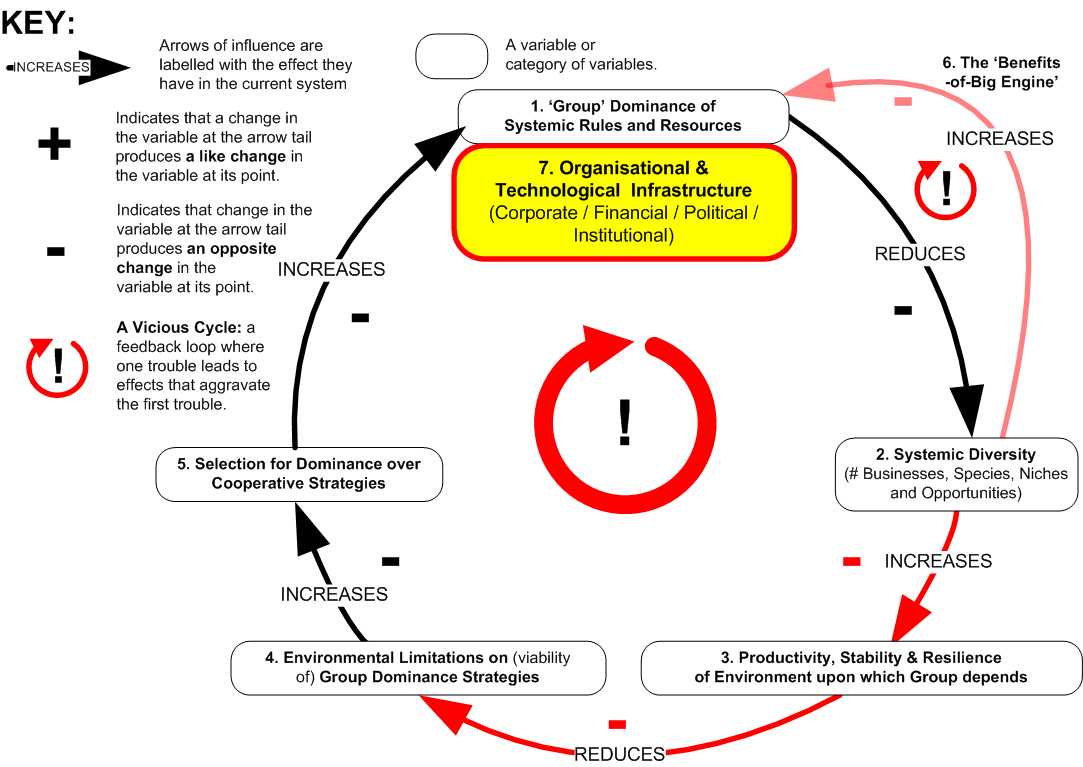

In installments 1, 2 and 3, we proposed that in natural / social systems a species or ‘group’ seeking total domination of their environment are constrained and, ultimately, destroyed by the impoverishing and destabilising effects of their actions on the systems upon which their own survival depends, thus leaving the arena open for dynamics that promote diversity and long-term stability (see previous installments if you need an explanation of the model below).

In installment 4 we suggested that the current economic system displays a reverse trend towards uniformity and instability because it allows the small ‘groups’ at the helms of corporations to gain increasing wealth and power from disintegrating social / natural systems without ever personally experiencing the environmental backlash of their actions. (see installment 4 if you need an explanation of the model below).

To clarify, this shouldn’t be taken as a demonisation of businessmen. Some individuals are naturally entrepreneurial, status-driven or materially-oriented, and the prosperity and order we have come to enjoy in recent centuries are largely indebted to their spirit and energy. Indeed, there are few among us that wouldn’t pass up a lottery win and the prestige, security and freedom it affords.

To clarify, this shouldn’t be taken as a demonisation of businessmen. Some individuals are naturally entrepreneurial, status-driven or materially-oriented, and the prosperity and order we have come to enjoy in recent centuries are largely indebted to their spirit and energy. Indeed, there are few among us that wouldn’t pass up a lottery win and the prestige, security and freedom it affords.

However, in the current era, unconstrained profit-and-power motivated vicious cycles represent a mortal threat to our freedom of choice, quality of life and, most urgently, our planet’s life systems. If the virtuous feedback mechanisms that promote diversity and stability in natural / social systems do not function naturally in the current economic system, then they they must be imposed artificially with due haste. But how?

First let’s summarise, in a nutshell, the problem to be resolved…

In the current economic system, dominant ‘groups’ are able to benefit from abusing the diversity and stability of socioenvironmental systems without ever experiencing negative feedback from their actions.

Although many possible interventions occurred to Arkadian whilst writing this series, a coherent regulatory model, which offered an unobjectionable, easy transition from the current economic system was not so easy to imagine (the reason why the final installment has been so long in coming!). Happily, a fully-formed (40yr old) solution presented itself recently in Chapter 19 of ‘Small is Beautiful’, courtesy of the genius of economist, E.F. Schumacher (pictured left).

The Schumacher Business Model, stated simply, rests on 2 systemic ‘tweaks’: (1) limiting the number of people a single corporate entity can employ and (2) introducing meaningful public ownership and accountability into business structure and practice.

(1) Legally restricting corporation size by number of employees. It would seem reasonable that a ceiling should be dictated chiefly by evidence regarding effective human group size (see Dunbar’s number), say between 80-200 persons. Growth beyond the upper limit, Schumacher suggests, should entail the formation of new independent corporate units, which may be linked by joint stock. These restrictions would enable each employee to ’embrace the idea of the business as a whole’ and the value of their role therein, but most importantly to the current argument, it would ensure that ‘the group (i.e. The Board)’ couldn’t claim ignorance of the details of their company activities and, thus, could reasonably be held personally accountable for abuses.

Furthermore, constraining size, particularly when the exploitation of natural / social resources is involved, is also more likely to physically ground a corporation in a local environment. Bringing ‘the group’ closer to their employees and the raw coal face of their realworld transactions is likely to increase their susceptibility and responsiveness to negative socioenvironmental feedback both internal and external to their organisation. It is also liable to curb the scale of impacts of which a single corporate vehicle is capable.

All very well, the cynics may cry, but what of the ‘groups’ with the thicker skins and thinner moral fibre?

(2) Public Ownership and Accountability. Schumacher advises we put an end to annual corporate taxation (a proposition not disagreeable to most businessmen!). In its place he proposes that for every share sold privately by a company, a further share is issued to the public. Thus, as owner of 50% of the company, we’d collectively receive half of any dividends if and when they are paid out to shareholders (he argues that when a company grows beyond a certain size it loses its ‘private and personal character’ and thus can be considered, in a sense, a public enterprise anyway).

To avoid disruption, our public equity wouldn’t allow us any voting rights in everyday business decision-making. It would, however, entitle us to attend Board meetings as an observer and, if the actions of the business were deemed to run counter to the public or environmental interest, we could apply to a court to get dormant voting rights activated.

To avoid disruption, our public equity wouldn’t allow us any voting rights in everyday business decision-making. It would, however, entitle us to attend Board meetings as an observer and, if the actions of the business were deemed to run counter to the public or environmental interest, we could apply to a court to get dormant voting rights activated.

To exercise these corporate responsibilities, Schumacher proposes the creation of independent citizen bodies funded from local business dividends. These ‘Social Councils’ would be split into four equal parts: three would have their members nominated by local trade unions, professional, and environmental, organisations, with the final quarter being drawn randomly from local residents in the manner of jury service. Involvement in management processes would, of course, be bound by strict confidentiality agreements.

Schumacher’s model brings socioenvironmental feedback directly into the Board room both as a ‘possibility in the background’ and, when necessary, as a real, prevailing constraint.

It is Arkadian’s prediction that, over time, exposing the ‘groups’ at the corporate helm to these balancing dynamics would drive a new trend towards macroeconomic diversity and stability, and greater corporate responsibility for the integrity of the natural environment (by triggering the ‘Diversity Engine’, described in installments 1, 2 and 3). And to top it all, it would require minimal design and economic / legal restructuring because, in the main, the model utilises existing frameworks and practices.

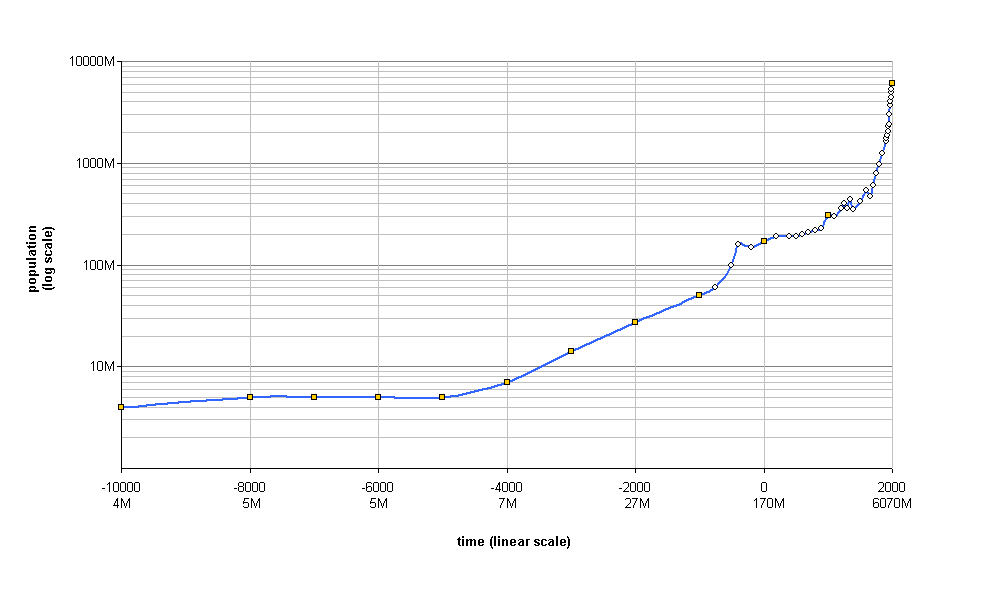

To conclude, effective corporate regulation is not just a Utopian nice-t0-have. It took till 1960 for World Population to hit 3bn. It has grown by 1bn approximately every 12yrs since, probably hitting the 7bn mark earlier this year. There are more human beings to house and feed today than have ever lived before. Presently, we have just over 2 acres of workable land each, 4x less than a century ago, and this is shrinking each moment as corporate activities and climate change destroy the natural world, and population continues to skyrocket.

Resultant biodiversity loss, whilst often second-ranked in current ‘problem’ trends is, as we’ve established, probably the most dangerous of all due to its inscrutable relationship with macroenvironmental instability. With extinctions currently at 1000x the background base rate, and predicted to rise to 10,000x over this century, we are very rapidly, and very blindly, removing the Jenga pieces of our life systems, largely for the sake of the short-term wealth creation of the small ‘groups’ of the corporate elite. History is littered with exemplars of total societal and environmental meltdown as the result of human impact on vulnerable ecosystems: Easter Island, The Mayans, The Pueblo Culture of the South Western USA, the Norse Greenland and Iceland colonies to name but a few. If we repeat the same mistakes globally, we may not get a second chance.

Resultant biodiversity loss, whilst often second-ranked in current ‘problem’ trends is, as we’ve established, probably the most dangerous of all due to its inscrutable relationship with macroenvironmental instability. With extinctions currently at 1000x the background base rate, and predicted to rise to 10,000x over this century, we are very rapidly, and very blindly, removing the Jenga pieces of our life systems, largely for the sake of the short-term wealth creation of the small ‘groups’ of the corporate elite. History is littered with exemplars of total societal and environmental meltdown as the result of human impact on vulnerable ecosystems: Easter Island, The Mayans, The Pueblo Culture of the South Western USA, the Norse Greenland and Iceland colonies to name but a few. If we repeat the same mistakes globally, we may not get a second chance.

Considering the twin pincers of population growth and biodiversity loss, it is quite evident that socioenvironmental stability and sustainability are our most important objectives for the c21st, bar none. Our very survival depends on achieving them and success is contingent upon economic and environmental policy which is underpinned by the principle of diversity=stability=good. If variety is both the spice and source of life, then we must put democratic pressure upon Government and business to make the small tweaks to our economic system necessary for it to produce abundance by its own workings.

For a fascinating and vitally important lesson in the importance of preserving and promoting biodiversity, Arkadian cannot recommend the video below more highly. Essential viewing for all inhabitants of Planet Earth.

Recent Posts

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 3: Placing Mother Nature First

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 4: Ego-as-Process

- Charlie Hebdo and the Immorality Loop

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt3 (S America: #2-1)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt2 (S America: #7-3)

- My Top 20 Waterfalls Pt1 (Africa, Asia, Europe & N America)

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 4: Principles in Action

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 3: Freedom from the Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles Pt 2: The missing Community Principle

- Positive Change using Biological Principles, Pt 1: The Campaign Complex

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 2: The Principal Themes (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- Seeding a Viable Economic Alternative. Pt 1: The Action Plan (Outcomes of a Systems Workshop at Future Connections 2012)

- What I Learned from Destroying the Universe

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 5 of 5: How do We Create a Diverse and Stable Economic System?

- The Root of all Evil: how the UK Banking System is ruining everything and how easily we can fix it.

- What is Occupy? Collective insights from a ‘Whole Systems’ Session with Occupy followers

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 4 of 5: Why does the current Economic System tend towards Uniformity and Instability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 3 of 5: Why does A Diverse System = A Stable System?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 2 of 5: Why does (did) Civilisation tend towards Diversity and Stability?

- Why Corporate Regulation is a Socioenvironmental Necessity. Part 1 of 5: Why do Ecosystems tend towards Diversity and Stability?